Ficus palmeri

|

Increase The Size Of Display On Your Monitor:

|

|

PCs Type Control (Ctrl) +

|

|

MACs Type Command (⌘) +

|

|

|

Two remarkable fig species in the Palomar College Arboretum are native to canyon walls of the rugged Sierra de la Giganta east of Loreto. These photogenic trees grow on vertical rocky slopes like waterfalls made of wood! Although I still refer to them by their old synonyms, they have been consolidated under a single species. As I have stated many times before, fig diversity, taxonomy, and ecological relationships with symbiotic wasps are the most fascinating & complex topics of my entire biological career.

|

Wild Figs (Higueras) in Baja California

|

© W.P. Armstrong 2011 (updated 22 August 2023)

|

|

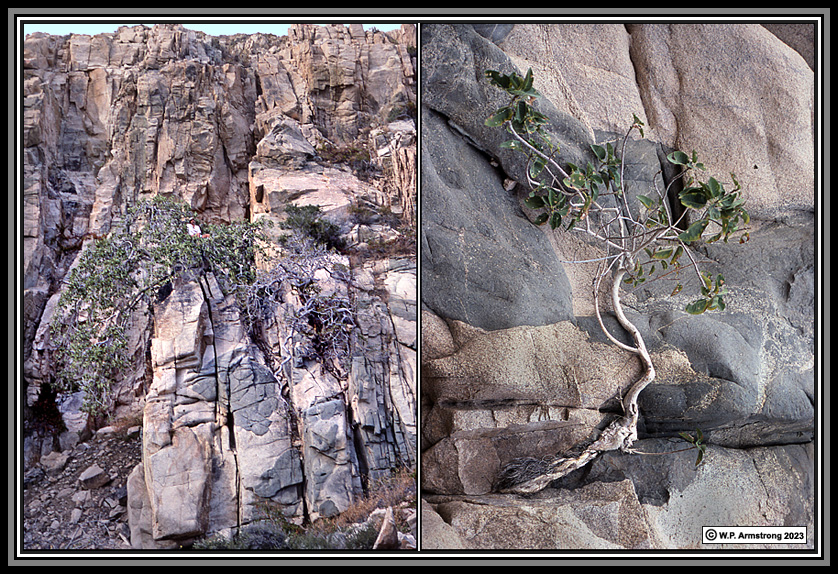

Many years ago I flew to a town called Loreto in Baja California with friend and Palomar student Steve Disparti. We got a ride to the base of the magnificent Sierra de la Giganta where we hiked for miles up a steep canyon. Our objective was to find the "Mexican rock fig" (Ficus palmeri) that literally cascades down vertical slopes with anastomosing branches like a massive botanical boa constrictor. We also found another similar fig with slightly different leaves that I identified as F. brandegeei. They both looked slightly different from a 3rd species with red-veined leaves on the mainland of Mexico (F. petiolaris). I was surprised to learn years later that they are now recognized as the same species. On this page I still include the historic synonyms from my original report; however, the correct, up-to-date, specific epithet is "petiolaris." We also found this magnificent fig on

other trips to the Sierra de la Laguna and Cabo San Lucas.

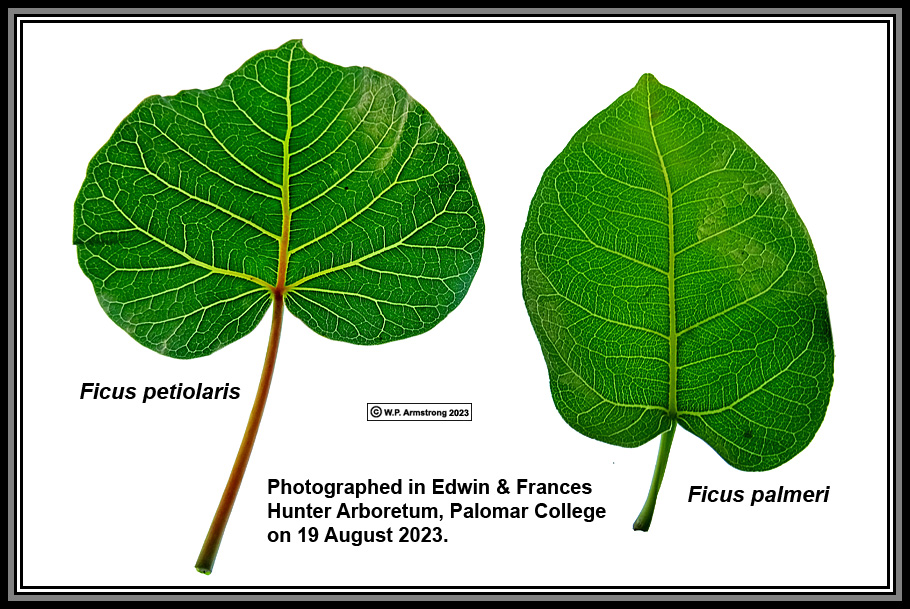

According to E.M. Piedra-Malagón, V. Sosa, and G. Ibarra-Manríquez (Systematic Botany 36(1): 80-87, 2011), Ficus petiolaris is the only species that should be recognized, with a wide distribution from Sonora to Oaxaxa and in Baja California. Some references consider F. petiolaris and F. palmeri to be subspecies of F. petiolaris. According to International Plant Names Index (IPNI) and Kew Plants of the World Online, F. palmeri and F. brandegeei are synonyms of F. petiolaris.

|

Rock figs of Mexico are considered a type of strangler fig. Tropical strangler figs seedlings start out as an epiphyte high on the branches of host tree. They eventually send anastomosing, aerial roots to the ground, completely enveloping the host tree. The following paragraph is from my Strangler Figs & Banyan article on Wayne's Word:

In their native tropical habitats, many figs are called "stranglers." Seeds germinate high on the moist branches of rain forest trees, sending numerous aerial roots to the ground. The sticky seeds are dispersed by a variety of fruit-eating birds and bats. Like botanical boa constrictors the serpentine roots gradually wrap around the host's limbs and trunk, crushing the bark and constricting vital phloem and cambial layers. The network of roots, resembling a tangle of writhing snakes, also fuse together (anastomose) forming a massive woody envelope or "straightjacket" encircling the host. Expansion of the host trunk as it grows in girth may accentuate the death grip and subsequent girdling process. Eventually the host tree dies of strangulation and shading, and the strangler fig stands in its place. In many cases the host tree may actually succumb from shading and root competition rather than strangulation. When strangler figs start in the ground, as in cultivation, their trunks develop from the ground upward like other "conventional" trees.

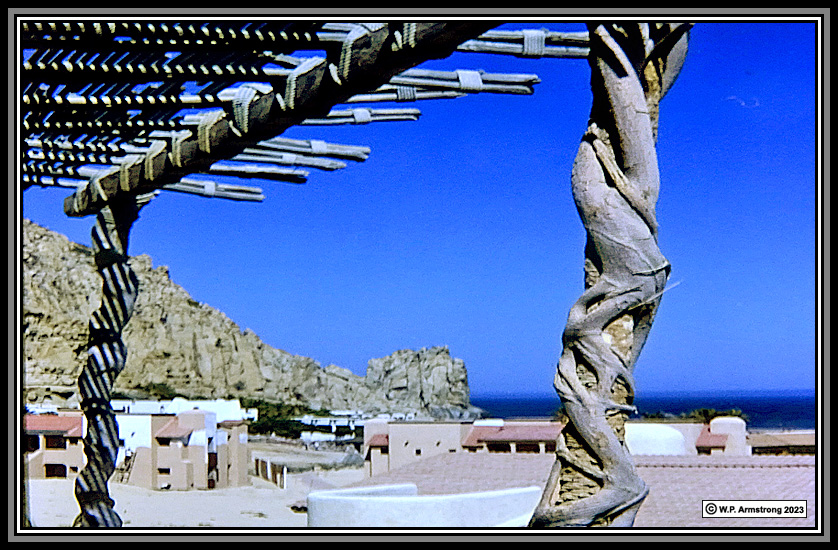

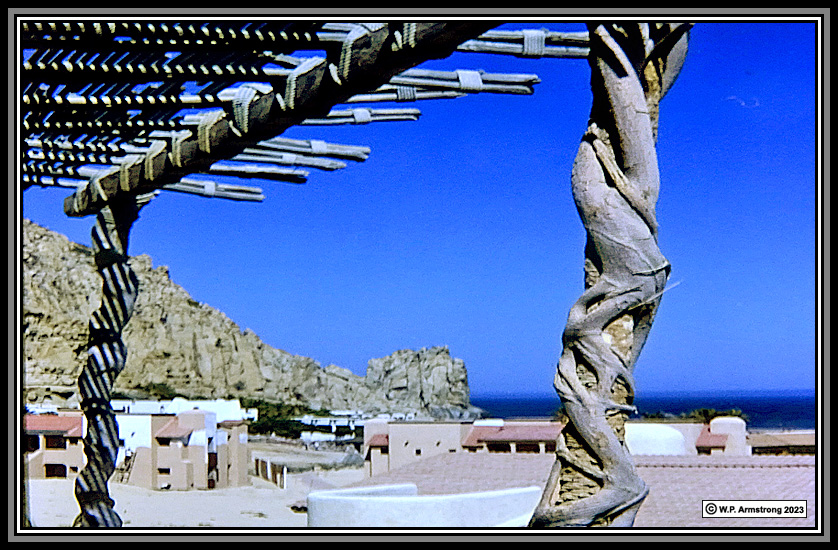

In the Cape Region of Baja California there are many palapas, traditional Mexican roofed structures supported by a palm trunk. They are common on beaches with a roof made from palm leaves or branches. The palm trunks are often encircled by a strangler fig resembling a botanical boa constrictor. Palm beams with strangler figs are also used indoors. In Central America, strangler figs are referred to as "matapalo" (tree-killer). The palm trunks are undoubtedly imported from the mainland, probably a tropical region.

|

Beach resort at Cabo San Lucus. The palm support pillar on this palapa is covered with a strangler fig. For this online image I photographed my 35 mm Kodachrome transparency directly on light box with Sony HX-60 digital camera. The image was uprezzed to 300 dpi with Genuine Fractals (Photoshop Plugin). I did not use a slide scanner.

|

Ficus palmeri

|

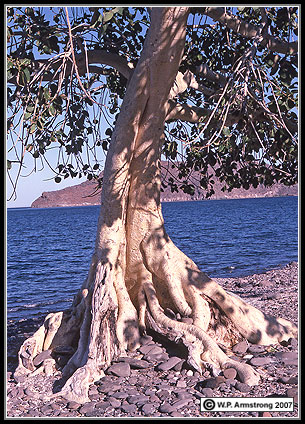

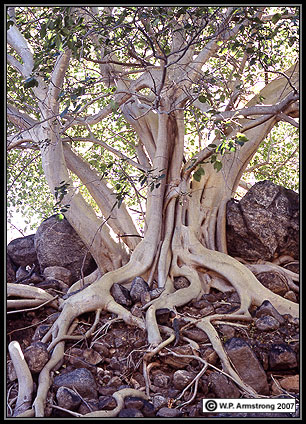

Ficus palmeri in Baja California. Left: Bahia Juncalito south of Loreto. Right: Sierra de la Laguna north of San Jose del Cabo. Note the numerous surface roots spreading outwardly in all directions. This same root pattern can be seen in the large Moreton Bay fig (Ficus macrophylla) near the San Diego Natural History Museum and in the Palomar College Arboretum.

|

|

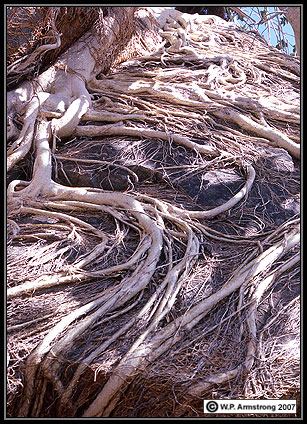

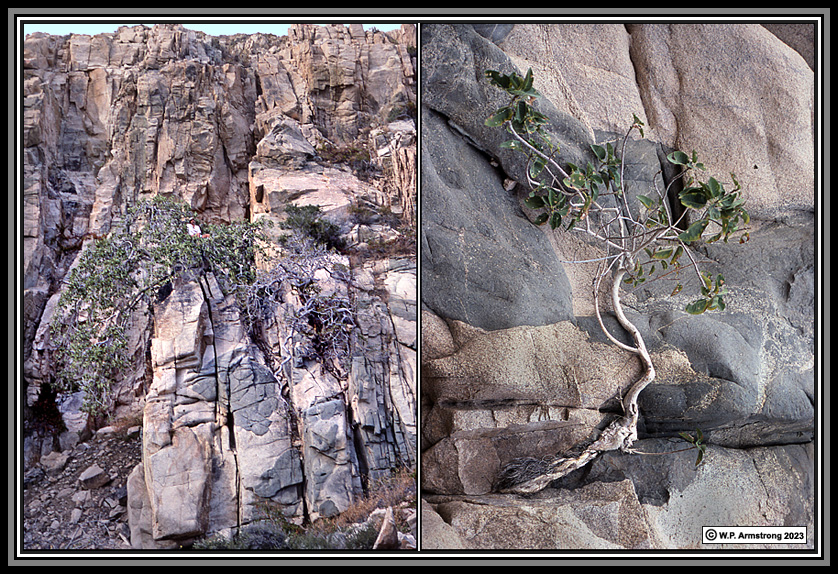

Ficus palmeri in Baja California. Arroyo southwest of Loreto in foothills of Sierra de la Giganta. The gray trunk in left image appears to have melted and flowed down the steep rock face like an arboreal waterfall. Actually, adventitious (aerial) surface roots from the trunk grew down the canyon wall and fused together (anastomosed). The aerial roots of tropical banyans form pillar-like prop roots that support the massive, spreading limbs. In strangler figs of the rain forest the aerial roots wrap around host trees like botanical boa constrictors.

|

|

Left: Ficus palmeri along the shore of Bahia Juncalito south of Loreto. Right: F. palmeri in an Arroyo southwest of Loreto in the foothills of the Sierra de la Giganta. Many of the figs in this region appear to be the closely related F. brandegeei rather than F. palmeri. Problem finally solved: They are all F. petiolaris!

|

|

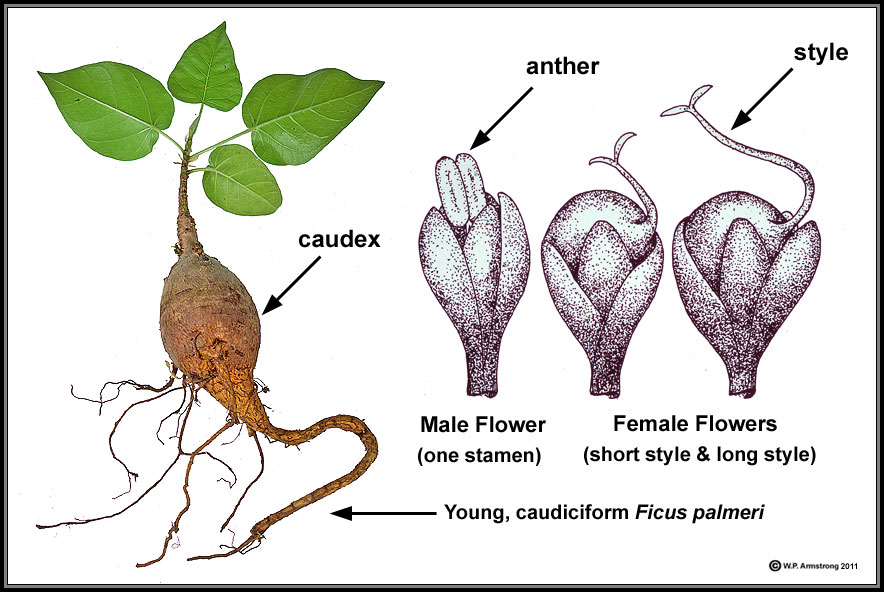

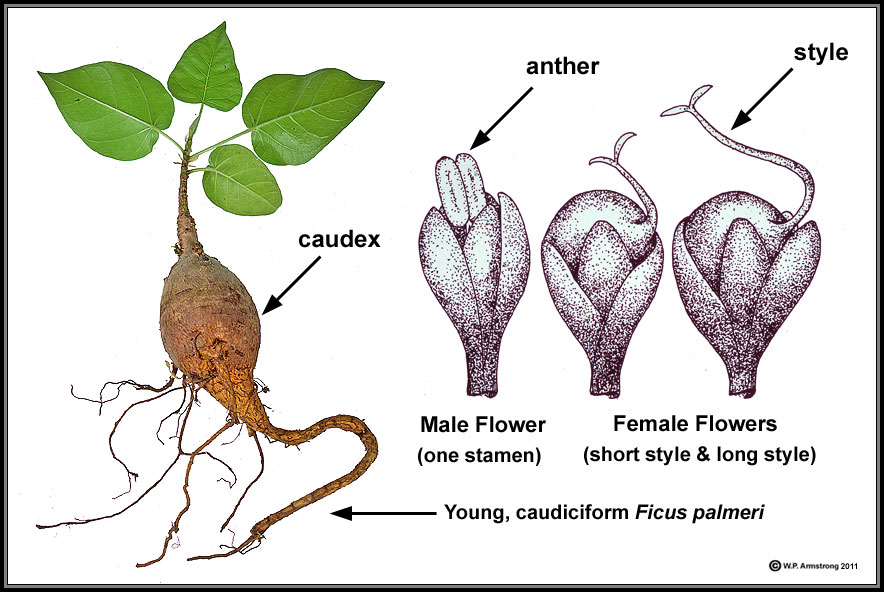

Ficus palmeri: Young caudiciform plant and illustration of flowers inside monoecious syconium. Figs of the F. petiolaris group (subgenus Urostigma) are pollinated by the wasp genus Pegoscapus (family Agaonidae).

|

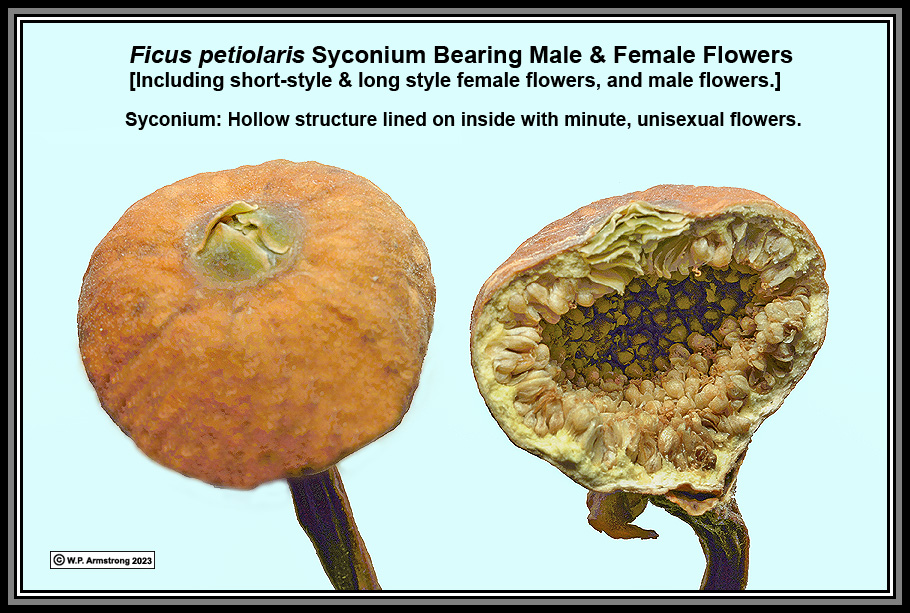

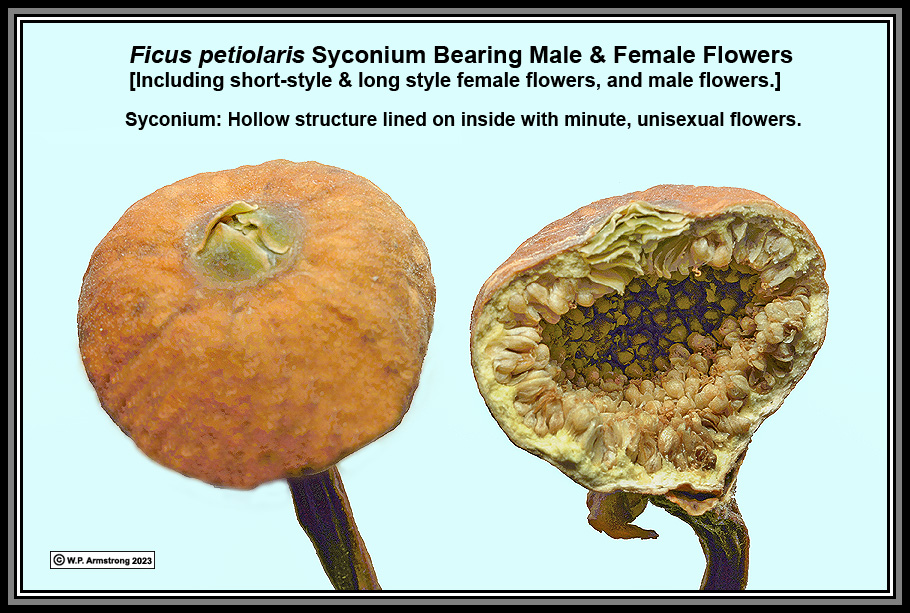

The above syconium is from the monoecious Ficus petiolaris in Palomar College Arboretum. F. palmeri and F. brandegeei are synonyms of F. petiolaris. The syconium contains both male and female flowers according to above illustration. Pollination did not occur because the symbiotic pollinator wasp (Pegoscapus) is not present. Consequently, no seeds were produced and all the syconia fell from branches and littered ground beneath tree. Monoecious is technically a species term. I suppose you say the syconium is "bisexual." About half of the world's 800+ fig species are monoecious, the other half being dioecious with separate male and female trees. Monoecious figs are considered to be the ancestral breeding system, dating back 70 million years when T-Rex walked on this planet.

In the dioecious, common edible fig (Ficus carica) there is a persistent allele (P) that allows unpollinated syconia to remain on the tree and become fleshy and flavorful. In fact, there are about 500 varieties with this persistent trait. Of course, without pollination the syconium does not contain seeds. The mutant, persistent gene is not advantageous to female fig trees, but it is a boon to fig growers because they get crops of tasty figs without the symbiotic fig wasp (Blastophaga psenes). Most fig connoisseurs agree that wasp-pollinated figs, with pollen from the male caprifig, are the best tasting. The seeds impart a delicious nutty flavor to the ripe syconium. In fact, a cutting from my remarkable 'Vista Caprifig' now grows near the Performing Arts Center on campus. Details of persistence and fig sexuality are explained on my fig page that is cited in many fig references.

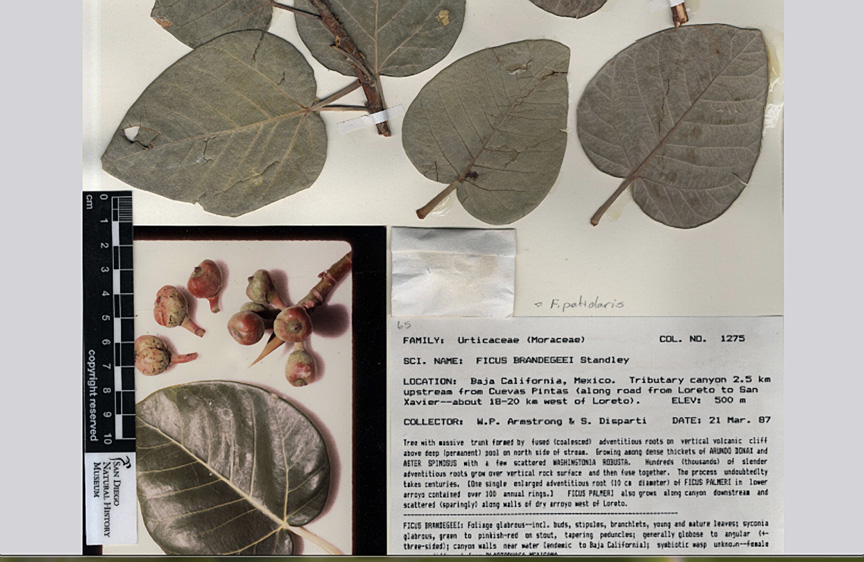

Ficus brandegeei

The general growth habit of this endemic species is very similar to F. petiolaris. Its leaves, branchlets and syconia are glabrous; however, in F. palmeri these structures are minutely pubescent (fuzzy). I always thought F. petiolaris was a mainland species east of the Gulf of California. Problem finally solved: They are all F. petiolaris!

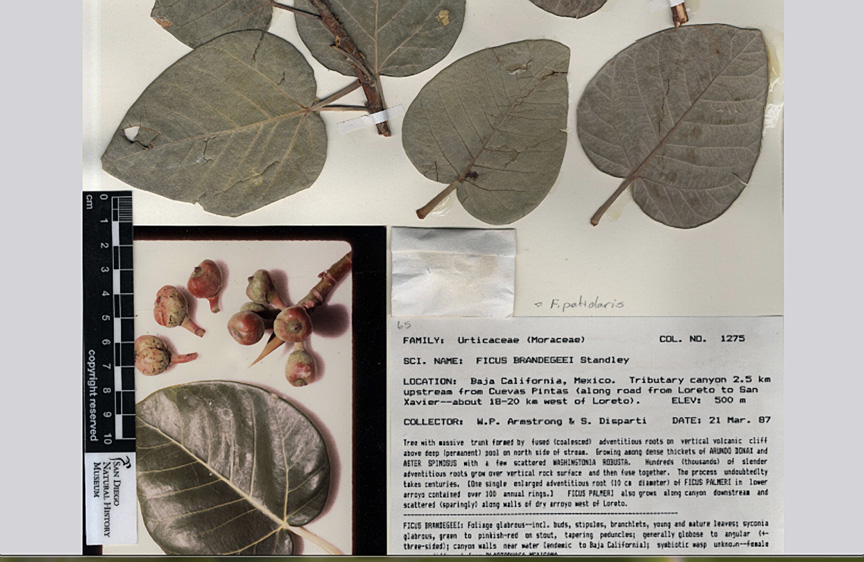

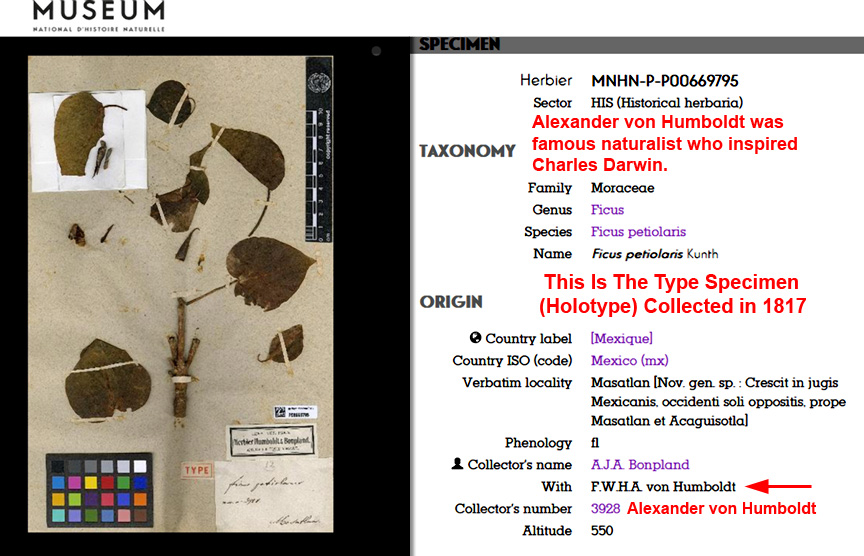

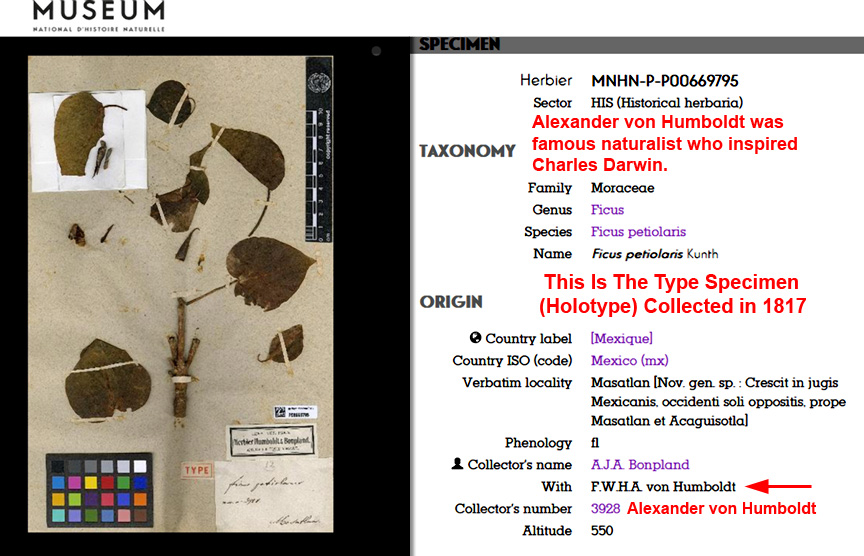

On my trip to the Sierra de la Giganta with Steve Disparti, I labeled our herbarium specimen Ficus brandegeei because it seemed to fit that species in the classic Flora of Baja California by Ira L. Wiggins; however, a type specimen (holotype) collected in 1817 is labeled F. petiolaris. During the past century, several names have been assigned to this fascinating fig, including F. petiolaris, F. palmeri and F. brandegeei. In fact, some authors have listed the latter 2 species as subspecies of F. petiolaris. The current taxonomic consensus is that they are all the same variable species of the 1817 binomial. The following is our herbarium sheet at the San Diego Natural History Museum compared with the original type specimen at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, France:

|

Ficus brandegeei in the Sierra de la Giganta, Baja California. The general growth habit of this endemic species is very similar to F. petiolaris.

|

|

Wild figs from Baja California: A. Glabrous syconia of Ficus brandegeei. B. Pubescent (fuzzy) syconia of F. palmeri. These are characteristics that separate the 2 species in The Flora of Baja California (1980) by Ira L. Wiggins. According to the current taxonomic consensus, these pubescent characteristics are within the range of variation within and between populations of F. petiolaris in Baja California & mainland Mexico.

|

|

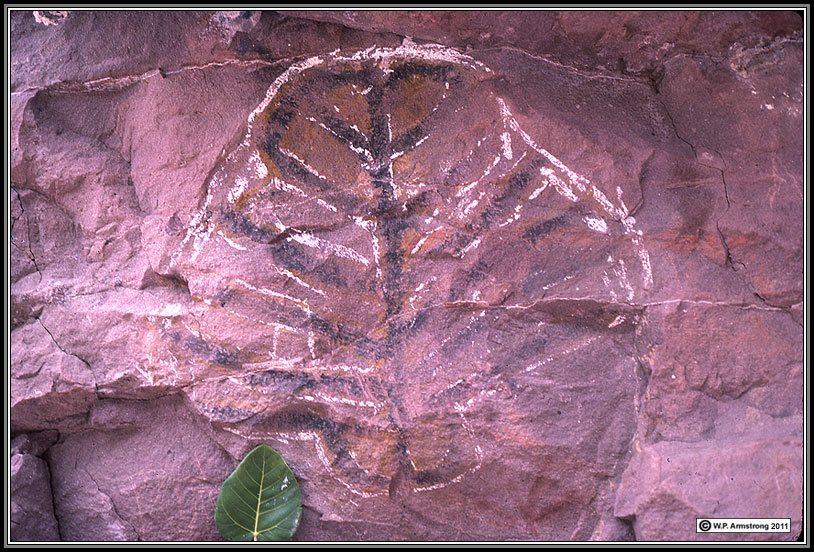

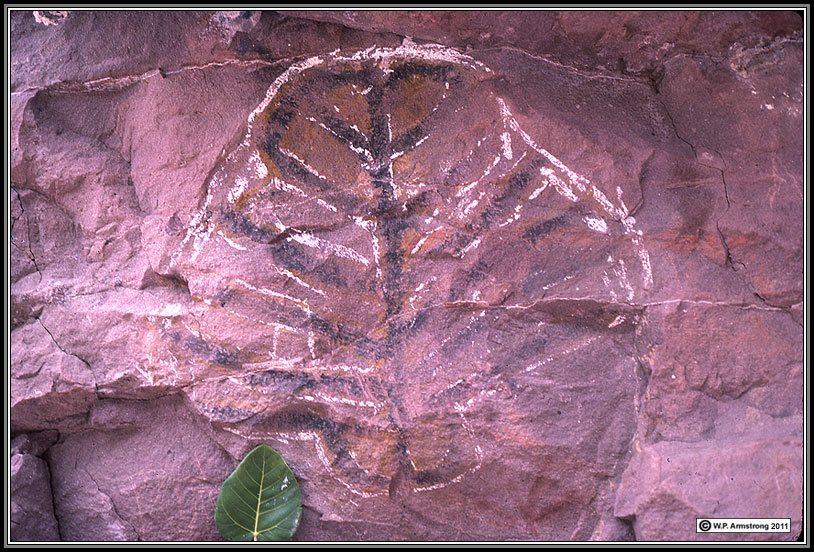

This pictograph (petroglyph) on a vertical wall in the Sierra de la Giganta superficially resembles the leaf of Ficus brandegeei that grow nearby. Its origin and meaning are unknown to this author.

|

|

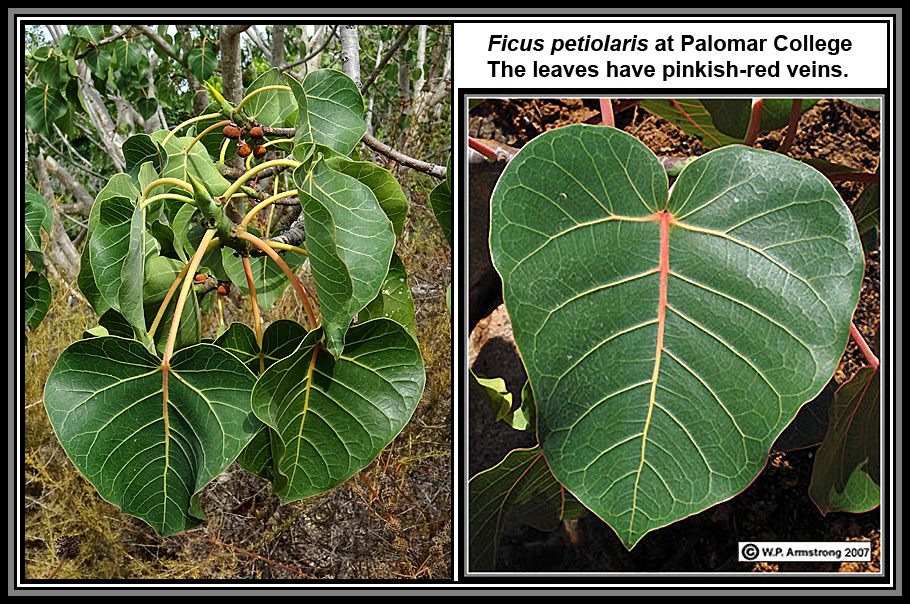

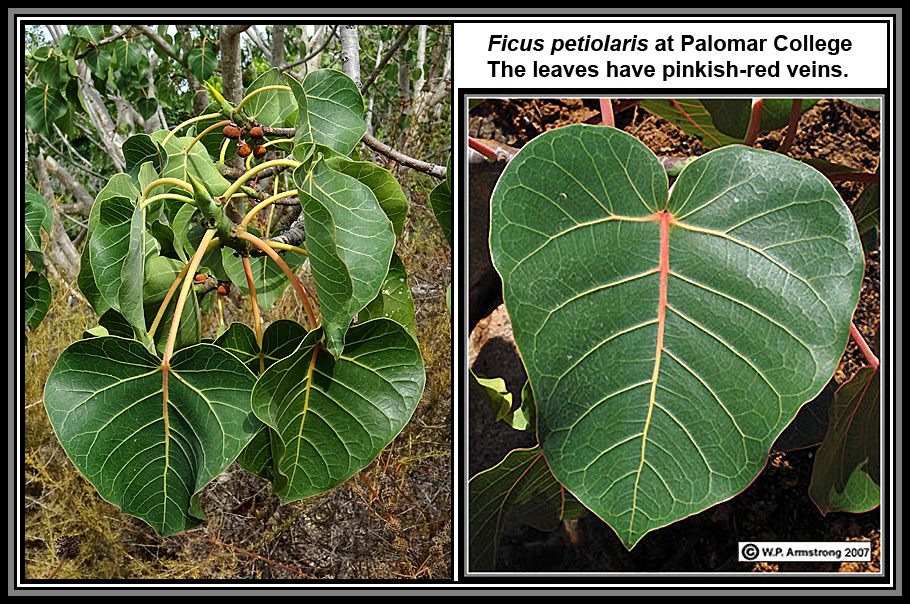

Ficus petiolaris in the Palomar College Arboretum adjacent to dense coastal sage scrub.

|

Ficus petiolaris

|

Ficus palmeri

|

Ficus palmeri

|

|

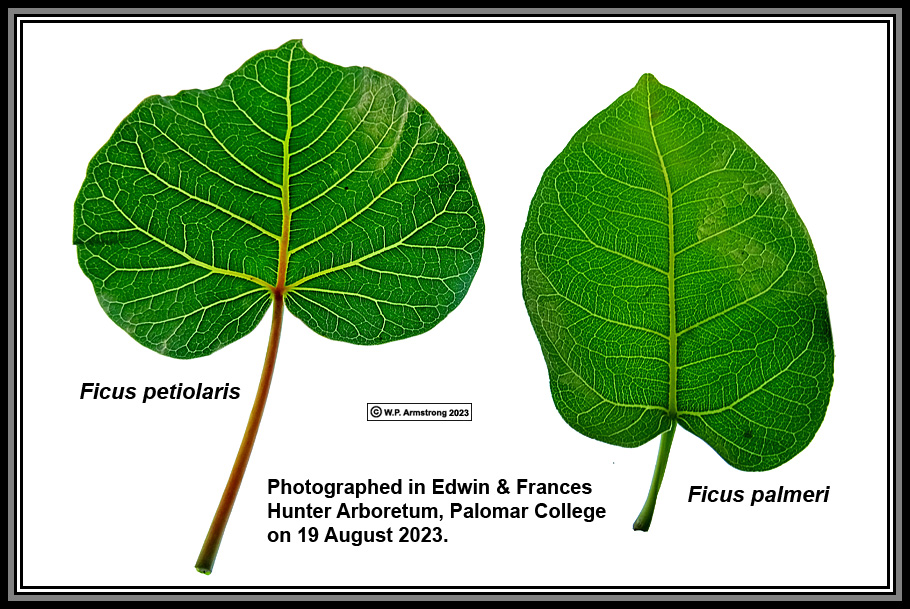

The leaves were photographed in the Palomar College Arboretum in 2007.

|

|

The leaves appear quite different in this recent image (19 Aug. 2023); however, apparently these characteristics are within the range of variation within and between populations of F. petiolaris in Baja California & mainland Mexico.

|

Rock Figs On Steep Slopes In The Cape Region of Baja California

|

Rocky vertical slopes in the Cape Region of Baja California have rock figs (Ficus palmeri = F. petiolaris). They are rooted in steep crevices and literally cling to the precipitous slopes.

|

Baja California began to separate from mainland Mexico about 8-10 million years ago. The disjunct distribution of rock figs Ficus petiolaris is undoubtedly explained by its widespread distribution on the continent of Mexico, from which the Baja California peninsula "drifted."

Index Of On-Line Fig Articles On Wayne's Word

|